The most commonly used sources of dispatchable renewable energy are reservoir-based hydropower facilities, which can be rapidly ramped up or down by grid operators depending on system power needs.

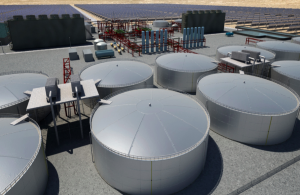

This week’s upbeat renewable energy supply outlook by the International Energy Agency (IEA) contained an important but overlooked lament about the slow roll-out of so-called dispatchable renewable energy sources. Other dispatchable renewable energy sources include geothermal, ocean, biomass and concentrated solar power installations, which can all have their electricity generation levels adjusted by utilities over the course of any given day.

The main takeaways from the IEA outlook were that renewable energy development has been supercharged by the fallout from the Russia-Ukraine war, and that green energy sources will overtake coal to become the main generators of global electricity before the end of the decade.

Other highlights included a more than doubling in solar and a 65% climb in wind generation within the next five years.

Pretty cheery stuff for climate watchers who have been alarmed by the accelerating pace of climate change and the continuing climb in fossil fuel emissions.

Somewhat buried in that buoyant prognosis for the world’s energy systems, though, were important comments about the comparatively slow deployment pace of renewable energy sources that can be dispatched on command into electrical grids to compensate for the intermittent nature of solar and wind power.

In contrast, a typical solar or wind farm can only generate electricity when the sun shines or the wind blows, and so are known as non-dispatchable or intermittent energy sources.

In an optimised renewables-based electricity system, dispatchable power sources may only be required in minimal amounts during periods of abundant solar and wind power generation.

But when cloudy skies or windless days kick in, these alternate renewable sources can be throttled up to offset the electricity shortfalls from elsewhere, and ensure that the overall system maintains the necessary power load.

That’s the plan on paper, anyway.

In reality, the IEA’s report this week highlighted that while developers of solar and wind installations are expanding at a record pace, growth in dispatchable supplies is flagging.

SLOW GOING

The IEA pointed out a slew of factors that have been stifling dispatchable renewable growth, including higher investment costs than for traditional wind and solar farms, and a lack of policy support.

And the development cost differences between a conventional hydropower plant with a storage reservoir and a comparably-sized solar farm are significant.

A 2019 study commissioned by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) found that a 100-megawatt (MW) hydroelectric power plant with storage reservoir would cost roughly $5,300 per kilowatt, while a 150-MW solar photovoltaic farm would cost around $1,300 per kilowatt.

In addition, development times can be far longer for hydro sites than for solar and wind farms, and the overall environmental footprint can be significantly larger on certain projects.

Geothermal plants and biomass power projects – which burn organic matter such as wood chips and household waste – can also cost more than twice as much as solar or onshore wind projects, according to the report, and can also be subject to opposition on environmental grounds.

Significantly, this week’s IEA report also claimed that «inadequate recognition of the flexibility value» of dispatchable renewables was another key factor hampering their development.

That statement implies that overall conditions could become more favourable for dispatchable renewable energy sources if their worth was better understood.

But the problem there is that different stakeholders can have conflicting viewpoints on renewable energy sites.

Climate-conscious energy consumers often embrace renewable energy supplies but oppose development plans that can impact the environment, ruling out the clearing of mountains and valleys for hydro-dams.

Project developers and big power users often prefer projects that are quick and cheap to complete, which currently favours solar and wind over other renewable options.

Governments – often the most critical stakeholder when it comes to energy infrastructure – tend to focus more on short-term energy supply needs rather than longer term energy system stability.

Ultimately, it may be the utilities that have the biggest direct impact on the prospects for dispatchable energy projects.

As the institutions most responsible for ensuring electricity supplies, utilities are best placed to see the merits of a system with a balance of cheap, intermittent renewables along with a complement of dispatchable assets.

With the IEA and others highlighting the vital role that dispatchable energy can play, more widespread support for the development of these strategic energy sources may now emerge, so that the greener grid of the future is also robust enough to withstand the odd but inevitable cloudy and windless day.

Significantly, this week’s IEA report also claimed that «inadequate recognition of the flexibility value» of dispatchable renewables was another key factor hampering their development.

That statement implies that overall conditions could become more favourable for dispatchable renewable energy sources if their worth was better understood.

But the problem there is that different stakeholders can have conflicting viewpoints on renewable energy sites.

Climate-conscious energy consumers often embrace renewable energy supplies but oppose development plans that can impact the environment, ruling out the clearing of mountains and valleys for hydro-dams.

Project developers and big power users often prefer projects that are quick and cheap to complete, which currently favours solar and wind over other renewable options.

Governments – often the most critical stakeholder when it comes to energy infrastructure – tend to focus more on short-term energy supply needs rather than longer term energy system stability.

Ultimately, it may be the utilities that have the biggest direct impact on the prospects for dispatchable energy projects.

As the institutions most responsible for ensuring electricity supplies, utilities are best placed to see the merits of a system with a balance of cheap, intermittent renewables along with a complement of dispatchable assets.

With the IEA and others highlighting the vital role that dispatchable energy can play, more widespread support for the development of these strategic energy sources may now emerge, so that the greener grid of the future is also robust enough to withstand the odd but inevitable cloudy and windless day.