DLR and the University of Evora are testing the use of molten salt in a solar power plant.

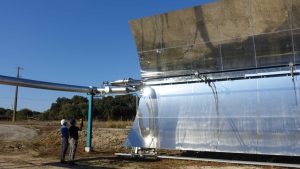

Engineers from the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum fuer Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) have taken an important step towards using molten salt as a heat transfer medium in parabolic trough solar power plants. Together with the University of Evora and industrial partners, a team from the DLR Institute of Solar Research has for the first time begun operating the solar field of the Evora parabolic trough test plant in Portugal with molten salt. This innovative technology is helping to further reduce the costs of operating solar thermal power plants. With their integrated storage systems, solar thermal power plants are the only technology able to generate large amounts of power from solar energy around the clock.

Salt offers higher efficiency as a heat transfer medium than oil

Current state-of-the-art commercial parabolic trough power plants use a special thermal oil as the heat transfer medium. The oil absorbs concentrated solar radiation collected using mirrors, converts it into heat and transfers it via pipelines to a heat storage unit or a steam turbine to generate electricity. The heat storage tank, filled with molten salt, can hold the thermal energy at temperatures of up to 560 degrees Celsius for a period of 12 hours and release it again when the demand for electricity increases. The power plant needs heat exchangers to transfer the heat from the oil to the salt in the storage tank, but some energy is always lost during this transfer before it can later be converted into electricity. The maximum possible operating temperature of the oil used is approximately 400 degrees Celsius, which limits the efficiency of the energy conversion. Researchers and industry are therefore looking for ways to further increase the temperatures in solar power plants in order to lower the costs of electricity generation.

One promising way to raise temperatures in parabolic trough power plants is to use molten salt not only as a heat storage medium, but also as the heat transfer medium in the collector field. Depending on the composition of the molten salt, it can withstand significantly higher temperatures than thermal oil – up to 565 degrees Celsius. Another advantage is that the storage tanks can be filled directly with molten salt from the solar field – eliminating the need for a heat exchanger.

In order to demonstrate this approach, the DLR Institute of Solar Research, together with the University of Evora and companies from Germany and Spain, has been building a solar parabolic trough test facility using molten salt as its heat transfer medium. The work started in 2016 and has taken place as part of the High Performance Solar 2 (HPS2) research project, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). The aim of the project is to demonstrate that parabolic trough power plants can be operated safely and economically with molten.

A technical challenge when using molten salt as a heat transfer fluid is that heating of all the pipelines is necessary. To prevent the molten salt from solidifying as the plant is filled, electrical trace heating must be used to preheat all salt-carrying components.

Successful initial filling and test operation of the system at 300 degrees Celsius

The collector modules of the HelioTrough® 2.0 generator from project partner TSK Flagsol, which are now filled with molten salt and connected to each other, provide a total thermal output of up to 3.5 megawatts across a total length of 684 metres. Currently, the plant operates with a ternary salt mixture from the project partner Yara, which has the advantage of a lower melting temperature compared to a binary salt solar salt mixture and can absorb heat up to a temperature of approximately 500 degrees Celsius. In addition to its use in solar thermal power plants for electricity generation, this salt mixture is also of interest for solar process heat supply systems.

Starting from an initial temperature of 300 degrees Celsius, the engineers want to gradually increase the operating temperature up to 500 degrees Celsius. In the coming weeks, the other components of the salt circuit will be brought into operation in Evora. In addition to the two-tank storage system, this includes the steam generator and the measurement equipment.

«We are very satisfied with the way the first filling went. Our next goals are to gain operating experience, fill all further components with molten salt step by step and test regular operations and also critical operating scenarios,» says Jana Stengler, head of the Fluid Systems Group at the DLR Institute of Solar Research, on the results of the initial testing.

The HPS2 plant is designed to also be operated with solar salt, a mixture of potassium nitrate and sodium nitrate, to achieve even higher temperatures of up to 565 degrees Celsius. Higher temperatures in the solar field allow for higher efficiencies in the conversion of solar energy into heat and heat into electricity, which lowers the cost of generating electricity.

«Power plants using the technology from HPS2 can be built more easily and operate more efficiently. This reduces electricity production costs by up to 10 percent,» says Mark Schmitz from the project partner TSK Flagsol, underlining the importance of the project for future solar thermal power generation. «That is an enormous step for a single technical change. At the same time, it makes longer storage durations of 12 full-load hours and more economically achievable.»

Sponsors and project participants

This research project is part of the ‘High Performance Solar 2’ research project funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (Bundesministerium fuer Wirtschaft und Energie; BMWi). The project is being monitored by Project Management Juelich (Projekttraeger Juelich; PtJ).

In addition to DLR, partners TSK Flagsol, Yara, Rioglass, Steinmueller Engineering, eltherm and RWE are involved in the project. The University of Evora, as the owner of the Evora Molten Salt Platform (EMSP), is supporting the construction and operation of the plant infrastructure with operating personnel and research staff.